March 26th 2007

Malcolm, a retired geographer, meets me off the train at Wareham and we drive West to Lulworth cove. In his company I can, incredibly, read the landscape. At Lulworth he points out the way the landscape crumples in waves. He shows me how to identify the major types of rock layers by their colour (green, white, red) and their texture.

Some rocks are soft and crumble easily like greensand (a very literal name this), the Portland Limestone is hard and massive with few cracks and fissures. I am surprised here to find that chalk acts as a hard, erosion-resistant rock. Close looking is required to distinguish a rock type with many fissures (the Wealden Beds) from one with less. Soon I can do this but it would have been impossible without Malcolm's intelligent eye.

We drive over the Lulworth ranges, a ridge of hard rock, part of the same crumpled wave we have seen in micro-scale at Lulworth, and into Kimmerage bay. Here there is a bay with softly shelving strata. Malcolm tells me that in the summer the rocky shelves forming the flat bottom to the bay warm up so a swim in the bay is far warmer than a swim elsewhere along the coast.

We walk Eastwards along the shoreline. The Kimmeridge clay is crumbling into the sea and we walk along among an abundance of fossils. I am very surprised to see a traditional nodding donkey oil well working on the opposite cliff. I thought these only existed in the deserts of America and Arabia - but it's got that same slow and simple jointed pump movement going on.

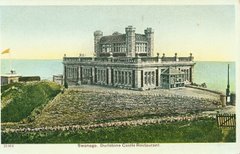

Finally we scramble down onto the strip of coast that faces Durlston Country Park from Swanage. Malcolm embarks on an incredibly detailed almost meter by meter examination of the rocks running along the coast. We see fossilied fish scales, the 'cinder-beds' which are ancient oyster beds, steak stone, and more else besides that I can't remember. It's amazing how a rather uninteresting, undramatic shoreline opens up like a book.

What do I take from this? Huge time scales, a sense of layering and buckling, close detailed differences. Causes and effects.

In the evening I meet Sam Gibbs. She works at the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton and has, luckily for me, agreed to be part of the project. She and I make a short presentation to a group and what hits me most in her presentation is that a chalk cliff - like the ones in view from Durlston - are 99 percent fossilised plankton.

Given that plankton are too small to be seen with the human eye a chalk cliff is a mind-boggling amount of time and bodies. Sam talks about how marine life fossilised like this locks up carbon. It is a process that takes carbon from the atmosphere and locks it away out of the system. This is what has helped to make the earth sustain life like ours.... that is until we came along and released it again by burning fossil fuels. Doh!

No comments:

Post a Comment